Beyond the landmarks, Beijing's mountains bring peace and serenity

Beijing is a treasure trove of imperial history and everyday life, layered across a vast and ever-changing city. For visitors with only a week or two in the capital, the sheer range of sights can feel endless. The Temple of Heaven, the Summer Palace and the Forbidden City reliably top the list, their grand halls and courtyards offering a sweeping introduction to China's imperial past. These landmarks deserve their fame, and most first-time visitors would be remiss to skip them.

But for those who stay longer, a different question eventually arises: What comes after the classics?

The answer, of course, may be to travel elsewhere. Few countries rival China for regional diversity, and a short flight or train ride can bring dramatically different landscapes, cuisines and cultures. Yet there are times when the desire is not to go far, but to simply go deeper. Beijing, for all its scale and modern sprawl, still holds quieter places tucked between hutong alleyways and mountain ridges. One such place is Lingyue Temple.

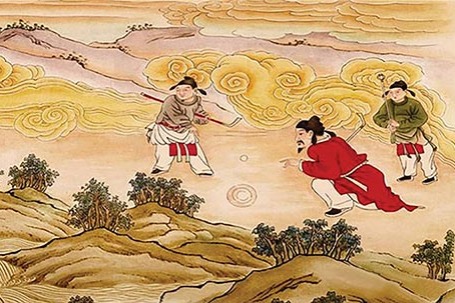

Located in Beijing's western mountains, Lingyue Temple dates back more than a millennium, first built during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) and later expanded in subsequent eras. Unlike the carefully restored temples within the city, Lingyue retains a weathered authenticity, shaped as much by time and nature as by human hands. It has never been a major tourist draw, and that is precisely its appeal.

A recent visit there with friends felt less like a day trip and more like an expedition. The road wound steadily upward, trading traffic noise for birdsong and herds of goats ambling across the pavement, a scene that felt worlds away from Beijing's ring roads. The mountains closed in, and the city slipped quietly out of mind.

The temple itself immediately felt different from its urban counterparts. The red of its walls had faded into a deep, earthy hue, softened by sun and rain. The wooden beams and eaves bore visible marks of age, their surfaces uneven and textured, a stark contrast to the polished symmetry of city temples that have undergone extensive restoration. Moss crept into corners. Stone steps were worn smooth by generations of footsteps.

Lingyue's layout follows the natural contours of the mountain rather than imposing a rigid axis. Buildings feel organically placed, as though they grew from the landscape rather than replaced it. The effect is subtle but powerful, especially as the sun sets on the mountainside, reinforcing the sense that this is a space meant for retreat rather than spectacle.

Walking through the grounds, the quiet was striking. There were no tour groups, no loudspeakers, no pressure to move on to the next photo spot. The stillness seemed to settle all around. It was easy to understand why films and television often portray mountain temples as places of inner calm. Here, that image felt less like fiction and more like possibility. Even the resident temple dog, wandering lazily around the grounds, appeared to embody a certain philosophical acceptance of the world.

I made the choice to do as little research as possible about Lingyue Temple beforehand, a decision that heightened the sense of discovery. At Beijing's famous sites, the experience is often shaped in advance by guidebooks, documentaries and social media. We arrive already knowing what to expect. There is pleasure in that familiarity, but also limitation.

Places like Lingyue invite a different kind of engagement — slower, quieter and more personal. They remind us that Beijing is not only a city of monuments, but also a place of margins and pauses.

For those willing to look beyond the obvious, the capital still offers moments of surprise. Sometimes, finding them requires nothing more than heading off the beaten track, slowing down and allowing the mountains to speak in their own quiet way.